Problematic Police Policies Pave Way for Violence, Corruption in Small Towns

The terms "Police Brutality" and "Excessive Force" have become part of the American lexicon in the last decade. Seldom does a week pass where those words are not splashed across a breaking news lower third, stinger or front page headline somewhere in the country. Many, if not most times, these stories find their way to the national stage sheerly because of the emotion and turbulance that follows.

Protest phrases like "Defund the Police" and "Hands up, Don't Shoot" have quickly developed into a national battlecry by protestors on the streets of major cities. Searing images of protestors squaring off with riot police, violence and even officers kneeling with protestors have ushered us into the biggest social movement of our time.

Calls to take guns out of the hands of officers, reallocate funding and develop human rights commissions abound, but what about policy? What role is policy playing in police violence? Does it help or hurt officers and the public they serve? Here, we take a look at one small town in West Virginia, and the role policies played in a series of events that ultimately resulted in a brutal assault, cries of corruption and federal lawsuit against the town and its police officers.

To understand how and why police procedure in general has dominated the news cycle, we need to look at the numbers. While no collective database currently exists to track every excessive force complaints, non-profits and watchdog groups have collected data on police killings through collaboration with journalists and police departments across the country. One reason for this is assaults or incidents that result in death are easier to track and thus, analyze.

Mapping Police Violence reports that police have killed 986 people in 2020 across the United States. However, all states do not score equally. If you break down the data during a larger window (2013-2019), New Mexico has the worst report card. 142 people were killed by police in a population averaging just over two million. That's an average killing rate of nine people per year for all people; however, it increases to a whopping fifteen people for the black population, versus only seven for the white population. In other words, black people are almost two times more likely to die at the hands of police in New Mexico than white people. You can see the top ten most deadly states by population on the left.

Police violence is widely perceived as an urban issue, but one look at the states to the left tells us otherwise. States like New York or California do not top that list; rather, we see states like West Virginia. In about seven years, police killed 74 people in West Virginia. Eleven of them were black. There, the average annual killing rate for white people was just over four people. For black people, it is 24. That means black people were over five times as likely than white people to die at the hands of police in West Virginia.

How can this happen? Partially, because there is little to no consequence for officers behind the guns. According to Mapping Police Violence, 98.3% police killings from 2013 through 2019 did not result in criminal charges against the officers. And while the case study below does not involve a death, it sheds light on why excessive force is used casually by police, especially in rural or small communities.

How could these deaths and assaults happen, with little to no repercussion for the officers involved? The simple answer is policy. While a majority of the public may condemn excessive use of force by police, policy creates vague protections for officers. According to police expert Dr. Jim Nolan, the events in Westover are a prime example of policy excusing egregious actions by officers.

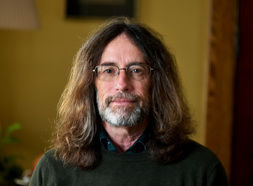

Nolan is a professor at West Virginia University and a retired police officer. During his time in law enforcement, he has worked as a police lieutenant, sergeant, and as a unit chief for the FBI Crime Analysis, Research and Development Unit. “Normal” is a word that came up again and again in Nolan’s evaluation of the video.

"They had to do something. But the way he handled it, I feel it is completely inappropriate. Completely unnecessary, but completely within the norms of police work.”

“This sort of violence is justified. You see, you ask the police if anything is wrong with it and they say ‘no, there’s nothing wrong with it.’ If you ask many police officers ‘Does this go against policy? They’ll say ‘no, it doesn’t go against policy. This follows policy. […] There’s assumption that if things are not right, then maybe someone is breaking policy. However, the truth is that even if police follow policy, they don’t create safety the way we imagine that they do.”

For some people in the small community just outside of Morgantown, the video points to a need for police reform within their city. It also makes Westover a microcosm of policy problems at large. The truth is, policy is meant to follow the law. If an officer's action does not violate policy, it will not violate the law. The cycle will continue.